Accent bias refers to the unfair or prejudiced treatment of individuals based on their accent.

Accent refers to pronunciation that is associated with a social identity, e.g., social class, region, age, etc. Since we’re all from somewhere, we’re all some age, and we’re all from a social class, we all have an accent. The notion of ‘accented English’ is a misnomer – all English is accented.

Bias is a natural human cognitive mechanism that helps us process a complex world efficiently and quickly.

Biases are not necessarily problematic. However, they have the potential to become problematic when people rely on these stereotypes to judge unrelated traits for instance, when people make inferences about someone’s intelligence or competence on the basis of accent. Using accent to infer this type of information results in something linguists call linguistic discrimination.

There is nothing inherently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about different varieties of language. All accents are legitimate and acceptable ways of using language. However, society does often make a value judgement about different accents: People perceive some accents as more prestigious than others.

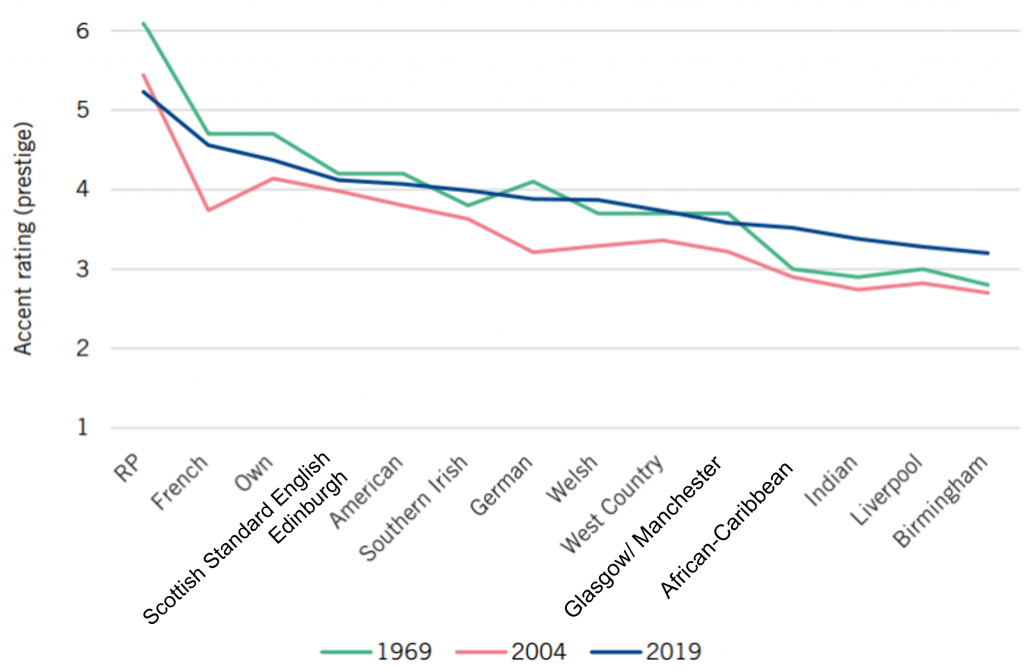

The Accent Bias in Britain project identified a ‘hierarchy of accent prestige’ that has existed for over 50 years. Standardised accents like ‘Scottish Standard English’ and ‘Received Pronunciation’ are valued as more prestigious than accents associated with ethnic minorities (e.g., Indian) and former industrial cities/towns (e.g., Glasgow, Birmingham).

Why should we care?

Accent bias can be a barrier to social mobility. In a recruitment setting, a candidate may be deemed less suitable for a position based solely on their accent – an issue particularly relevant to ‘elite’ professions like law, medicine, or finance.

Currently, neither accent, language nor social class are ‘protected characteristics’ under the Equality Act 2010. People can legally discriminate on the basis of linguistic difference.

This is an issue we’re tackling in the context of Higher Education, specifically universities. Here, accent bias may impact a student’s engagement with their studies, and their sense of belonging at the university.

Can’t people just ‘code-switch’?

A common proposal is that people could just change their accent to avoid any potential reprecussion for speaking with a stigmatised accent. In media, this is often referred to as ‘code-switching’ whereas in sociolinguistics, we refer to this as ‘style-shifting’. We all style-shift to some degree. For instance, most people will speak in a more formal style in an interview or at work and use an informal way of speaking at home.

But applying this logic in tackling accent bias is flawed for the following reasons:

- Changing the way you speak is not like changing your clothes. Often, our accent is hard-wired into us from a relatively early age. It is very difficult to change the way we speak. We can’t just drop an accent if we want to.

- We shouldn’t have to change the way we speak. There is nothing ‘wrong’ or ‘incorrect’ about different varieties of English. Society should be more accepting of linguistic diversity. The onus should not be on individuals to change their natural accent.

- Changing your accent may be only half the issue. Identities like ‘working-class’ or ‘gay’ are only partly constructed through language. People will likely be read as ‘working-class’ or ‘gay’ even if they are not heard as such.

- Your accent is your identity. If you do successfully manage to change your accent, you may feel like you’ve lost a part of your identity.